A thank you to the Glasgow Royal Infirmary

Losing a family member was made easier by compassionate care

I lost my uncle David Kemp this weekend. I will miss him dearly but it is some consolation to know that his care in the Glasgow Royal Infirmary could not have been better.

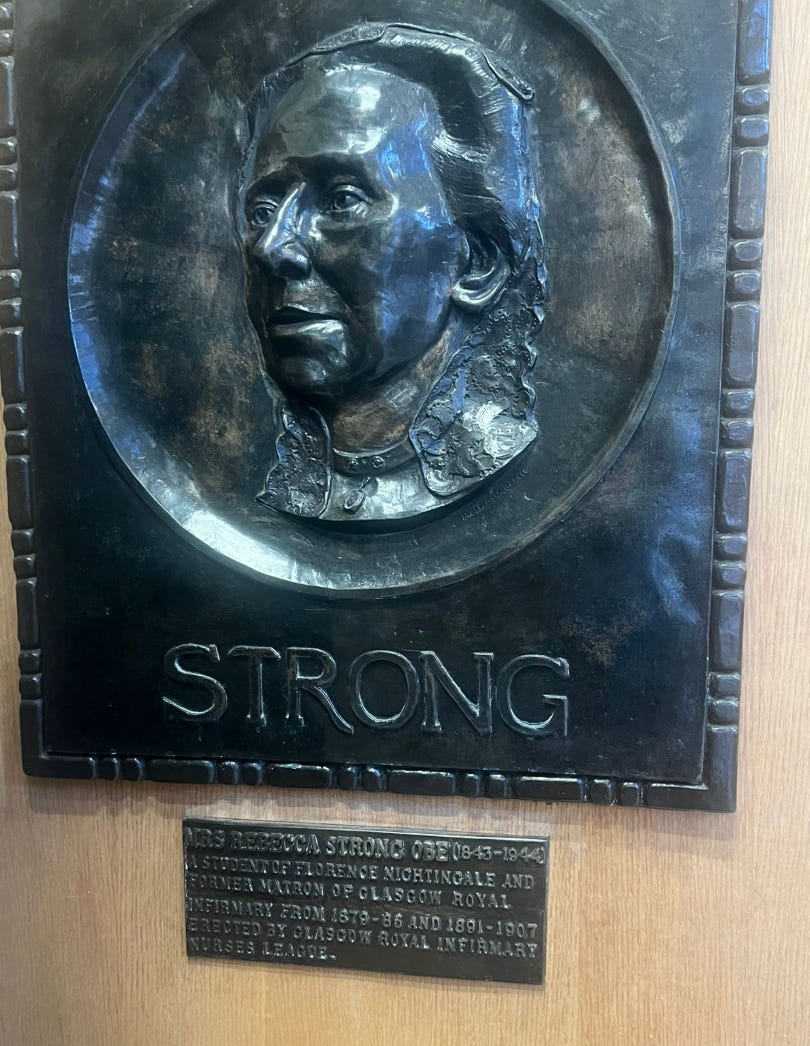

I spent the day of the Great Storm of 2025 in the belly of the GRI, in the ‘new building’ which was constructed at the turn of the 20th century and whose smoke-blackened turrets greet you as you turn off the motorway at Springburn.

All buses and trains were off and the streets were empty except for the occasional piece of spreath birling past. There was a red warning of danger to life and limb, yet I think every member of staff on David’s ward made it in to work that day. Some drove, some walked. One nurse I spoke to said a gallant neighbour gave her and her colleague a lift.

Glasgow has retained its Infirmary on the large East End site where it was founded in the 18th century. I have been many times to visit David on various sojourns there over the last 20 years - his heart stopped five times in one night when he was in intensive care with a catastrophic infection back then. For the next decade or more he walked up each Christmas to give the staff a gift.

One of the hospital’s strengths is that it remains in the beating heart of the city. It is part of the community it serves and can draw on a pool of terrific staff, many of whom live near by.

They were in and out of David’s side room in his last days making sure that he was as comfortable as possible. A nurse from another ward where he had been recently came up to visit him. They also often found time to offer me a wee cup of tea or ask how I was.

David had been seriously ill for a few weeks. On Xmas Day when my husband Rob went to collect him, he found him in a bad way and called 999. The ambulance took just 20 minutes to arrive and David was in a bed on a ward a few hours later.

Despite his increasing frailty, David remained compos mentis and on that hospital stay he asked for ‘Precipice’, the sequel to the Robert Harris book and recent movie ‘Conclave’. The book - not as good as Conclave apparently - is set against the background of World War 1 and so he asked for Margaret Macmillan’s book ‘The War that Ended Peace’ to be brought from his flat to re-read.

After about ten days, David appeared to be on the mend and was sent home with carers coming in three times a day. But it was not to be. Pneumonia added itself to the growing list of ailments and he was brought back in to the GRI

I was on holiday but flew back early when I heard David was worse and arrived just before the storm at Glasgow Airport. He seemed settled and not obviously in discomfort but only semi-conscious. I sat by his bed, reading the two books he gave me for Christmas, Timothy Garton Ash’s ‘Homelands: A Personal History of Europe’ which David loved and the thriller ‘The Damascus Station’ by former CIA analyst David McCloskey.

The shop in the new building was closed on the day of the storm but a note read that the WH Smith in the Queen Elizabeth Building was open, so I braved the Link Corridor. It wends its way to the Queen Elizabeth building (which in typical Glasgow style has no pedestrian crossing at its entrance on a major road, so you can often see wee women with toddlers and prams jinking across the traffic to catch the bus on the other side. Training starts early. )

Google says that the longest hospital corridor in Europe is in Wales - someone at the GRI should get the pedometer out and challenge that. The Welsh one is an art gallery displaying 80 paintings. The Glasgow one is an art installation. At one end it has signs to the Princess Royal Maternity Unit and then at various points along it are paper signs with the word ‘Mortuary’ and a blue arrow. You are born and then you die

The corridor is in several sections. It is immensely long and very spooky. At certain points there are mirrors so that you can see whoever is coming towards you - unless of course they have no reflection.

The day of the storm someone must have opened a door in a gust and some dead leaves had blown along the corridor, probably from the cemetery behind, and were sitting in a wee pile at the entrance to the mortuary.

When I got back from my trek, with a sandwich and a pile of newspapers, I was taken aside by a consultant and a trailing student to be told there was no more they could do for David. I already knew it and responded that I had heard pneumonia called ‘the old folk’s friend’. The consultant paused to explain this to the student - a medical term she had not yet heard. I phoned David’s cousin Prue King who reminded me of the satirical instruction to doctors by Victorian poet Arthur Clough: ‘Thou shalt not kill but need not strive/ officiously to keep alive’. This too is the doctor’s duty.

Despite everything we hear about the state of the health service, my uncle’s care was compassionate and professional, even in the most difficult circumstances. So I would like to say a public thank you to the staff of the GRI.

David Kemp’s funeral will be on Saturday, February 8 in Glasgow. The funeral service will be at the Robert Adam Room in the Trades Hall, Glassford St, open from noon, service at 1.15 pm. All welcome.

If you wish to attend the quiet cremation service, that will be in the small chapel at Glasgow Crematorium at 11.30 am, also on Saturday, Feb 8.

One time when my son William was visiting David in the evening he asked him to go get some cabs of diet Fanta or st and when Will was at the shop David got moved from one end of the hospital to the other. Will called me from the Link corridor and we agreed it was the spookiest place.

Condolences frae ane o' Prue's wee loons.....

The "old folks' friend" or "patient's friend" was a comment from mum's folks, Archie and Nannie, both GPs in Aberdeen....

Have said a prayer.....

Fergus