As ye sew: Scotland's medieval vestments

Embroidered garments for religious ceremony have a long history

I happened to be at the Colosseum in Rome on Thursday evening, watching a wee girl dancing to a busker playing ‘Stairway to Heaven’ on the saxophone, when I got a notification on my phone about the white smoke. I decided to walk across the city to St Peter’s - by the time I got there, the huge crowd was moving the other way as the new Pope had already made his debut on the balcony.

It was immediately noted that Leo XIV wore the traditional purple stole with ornate gold embroidery that had been laid out for him, unlike Pope Francis who went for simple white. When I saw the images on my phone, I thought - whoever sewed that is feeling pretty chuffed right now.

In Venice and Rome the preceding few days, I joined long queues to file past wonderful paintings, murals and statues- and it strikes me that while we revere other religious art, we don’t pay as much attention to the ancient art of the embroiderer. Their works don’t carry signatures. They are often produced by many hands - generally female hands. Perhaps that is why we don’t appreciate them in the same way.

I was thinking about this form of art because I visited my relative Prue King in Aberdeen recently. She makes and repairs vestments - even now in her 80s she is repairing a cathedral banner.

For Prue, vestments play an important role in the rituals and ceremonies of the Church. She explained that for medieval worshippers, listening to a priest preaching in Latin, a language they may not have understood, that role would have been even greater. The vestments are rich in symbolism, sometimes telling a Bible story in pictures. They were bright and beautiful to look at, to help the priest hold the attention of the congregation.

For the stitchers, sewing religious garments was an opportunity to use the best thread, the best fabric, and to direct their skill and artistry to important work. As early as the seventh century, nuns were making vestments and were at one stage accused of spending too much time at their stitching and not enough on prayer or study. One abbess vigorously defended them by saying that her sisters were counteracting the effects of idleness which led to evil.

Not all embroiderers were doing it for religious reasons - some were employed and it was a rare way for a skilled woman to earn a relatively good wage. Men were Broderers too and some guilds were male-only.

Prue made a study of Scotland’s surviving medieval vestments while she volunteered for nearly two decades at Blairs College Museum. The College, once a hub of Scottish Catholicism, closed in 1989 and stands empty, various plans to do something with this magnificent Victorian building having fallen through.

The Museum remained open until a couple of years ago. The vestments are now in store, intended for a Catholic Heritage museum planned for Glasgow. Prue would like to see them displayed again at some point in the North East, their home for so many centuries.

The most significant is the Fetternear Set. In a paper she co-authored, Prue makes the case that these vestments were commissioned by Count James Leslie and stitched by Hungarian nuns in the Ursuline convent of Vienna, incorporating war booty taken from the Turks.

The Leslie family were among the most successful of Scotland’s military diaspora. Five generals of the name of Leslie commanded the armies of four different nations – ‘Scotland, Germany, Sweden, and Russia – nearly all at the same time in the seventeenth century. One of them was Count James Leslie in the Habsburg Empire.

In 1683, the army of the Ottoman Empire laid siege to Vienna for two long months. The siege was broken by the Battle of Vienna in which Leslie, the general in charge of artillery, played a significant role.

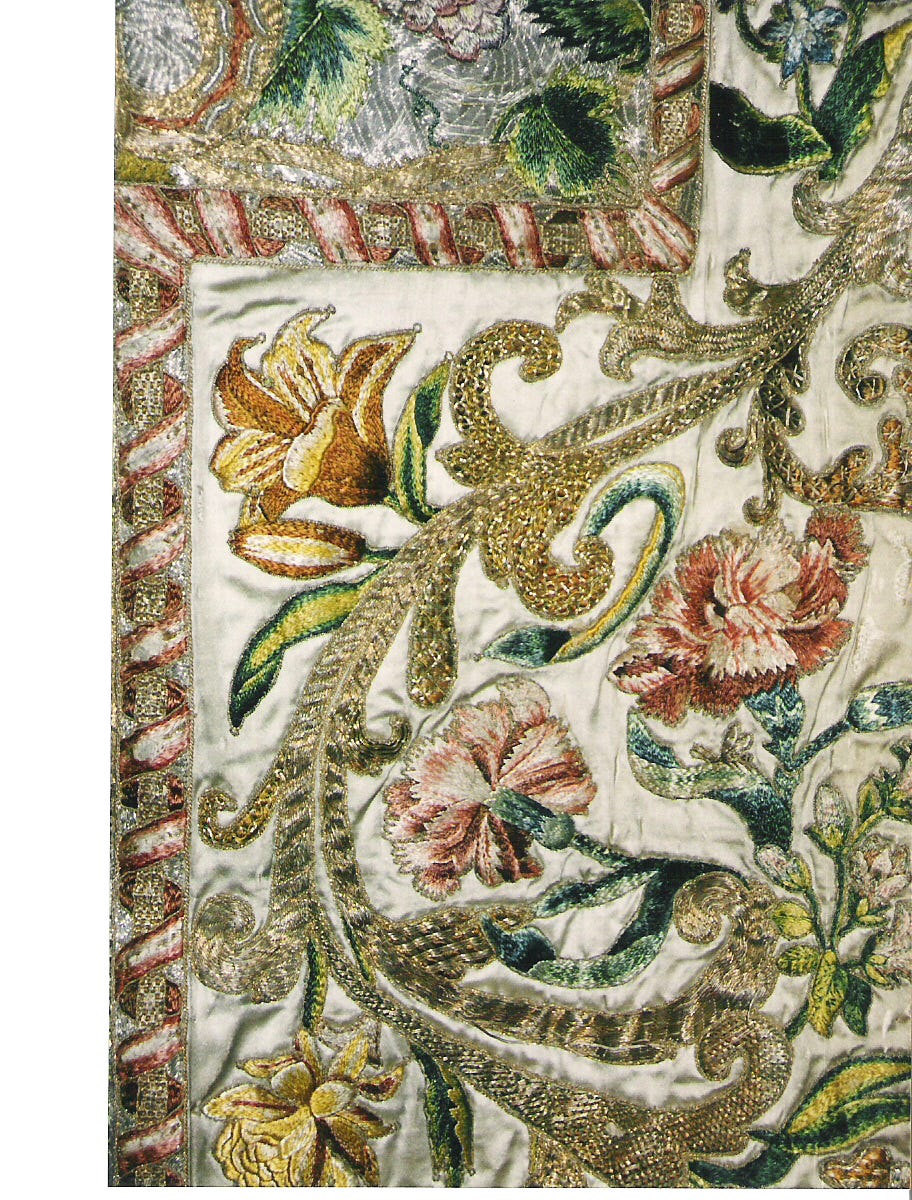

Prue’s paper says that the gold work in the Fetternear vestment set ia typical of that made by a fraternity of Turkish embroiderers of Istanbul: “Gold plate, flat metal with a ribbon effect, laid in strips over a padded silk ground, tied down with diagonals of fine thread and topped with coils and scrolls… ‘added lightness and texture to the embroidery and a touch of brilliance when worked in metal thread and plate.’ It was one of the highly prized crafts in Ottoman times…. The artistry of the worker has to be seen to be believed, it is no wonder that their work was so highly prized.”

She argues that this work was taken from an item seized at the Battle of Vienna and was likely handed over to the Ursuline sisters by Leslie to make into vestments. The nuns carefully removed the gold work from its original ground as slips or pieces which they then incorporated into the elaborate symbolic design of the finished vestments.

The Reformation hit Scotland late - but hard. Many artefacts - including the tombs of the Stuart Kings - were destroyed. The North East, however, remained more tolerant and less divided by factional religious hatred than other parts of Scotland, and the Leslie family were allowed to maintain their faith without interference - they had a separate door for estate workers to come to Mass at Fetternear House. The Fetternear Set like other precious things was preserved there for centuries.

Another is an ornate white vestment with a central panel which tells the story of St Anne and Joachim and the birth of Mary. It dates from the late 15th or early 16th century and may be Flemish or English in origin. It may have been saved from the Reformation by the chaplain of the Tailors’ Guild of Aberdeen. He was also a priest at Kenmay which is close to Fetternear. Prue thinks that this vestment was laid on a new ground for display at an event in Aberdeen in 1858.

Another prominent North East Catholic family, the Lumsdens, donated several items to the museum. One was not completely saved - the faces of the figures on the Corgaarff vestment have been attacked or scored out. The story goes that this vestment may have been retrieved from the walls of Tillycairn Castle when it was being restored.

The Lumsdens also bequeathed a vestment believed to contain some embroidery by Mary Queen of Scots while she was in jail. It doesn't use the typical religious iconography of the time, so it could be something that was repurposed, or done in a way to hide its intent (my fanciful speculation): Prue said: “Traditionally it was believed in the College that this was the work of the Queen as the central panels in the chasuble are of the correct period and style of embroidery. The main body of the vestment is of a slightly later date. It came to the College from the Lumsden family, so perhaps a cherished relic of the Queen’s work was made into a vestment using similar embroidered draperies for most of the bodywork.”

Scotland’s small stock of medieval vestments are part of a long tradition of religious figures wearing garments embroidered with symbolic designs. They are laden with tradition and story. Hopefully one day soon they will be on show again. The National Museum of Scotland managed to get hold of one - the Fetternear Banner - but it should be displayed with the rest of the collection.

Back in Rome, inspired by my young friend Luca (see last week’s blog) I was navigating my way around Rome with a paper map rather than sheepishly following an arrow on my phone. After a 45-minute march away from St Peter’s Square imagine my surprise when I came round a corner to find - St Peter’s Square. Darkness had fallen and most people had left - except media from all around the world, waiting their slot on flagship news shows - an Italian journalist crouched down to write her piece to camera with a pen and paper.

When Pope Leo leads his inaugural Mass on May 18, the embroidered vestments he wears will be seen by millions and they will acquire a historical and symbolic significance of their own. The hands that made them will remain anonymous.

I got this comment by email from Heather Swinson: Loved that article on embroidery! The earliest reference to embroidery I know of is biblical. The curtains of the temple which were very heavy and embroidered with cherubim , I think ( will check that out), were torn from top to bottom at the moment of Christ' s death signifying his sacrifice meant that access to God was possible because of the price he paid.

What a fascinating insight into a craft that was once so important, and one that I've never really thought much about -- until now.