Why does Scotland place so little value on its wool?

“Hey ‘Shetland’ - where’s the knitted headgear?”

“Hey ‘Shetland’ - where’s the knitted headgear?” Shetland-based Tom Morton wrote in a review of the new series and now I can’t unsee it. Whenever a trailer comes on for the latest series of the detective show it leaps to the eye. No hand-knitted woolly hats in sight. I read a feature in which the actor Ashley Jensen was complaining about how cold she was during filming - do she or the BBC costume department not know that 9/10 of body heat is lost through the head?

The controversy - if we can call it that - touched a nerve with me because I feel so angry about how little value we place on wool in Scotland. Of course the Scandis do this better - in the Danish series ‘The Killing’ the star of the show was the black and white fisherman-style jumper the lead detective wore in every episode. I remember my sister saying she had tried to watch the US remake but had to give up - the jumper was polyester.

More recently, Norwegian Wool has featured in Succession - a coat that Conner refuses to check at the door of Ken’s birthday party because “I don’t trust those things. I lost a ‘Norwegian Wool’ in a fusion restaurant in Vancouver.” Now that is product placement. The New York Times called the Norwegian Wool coat, which is waterproof and costs about £1,500, “the coat to wear to Davos.”

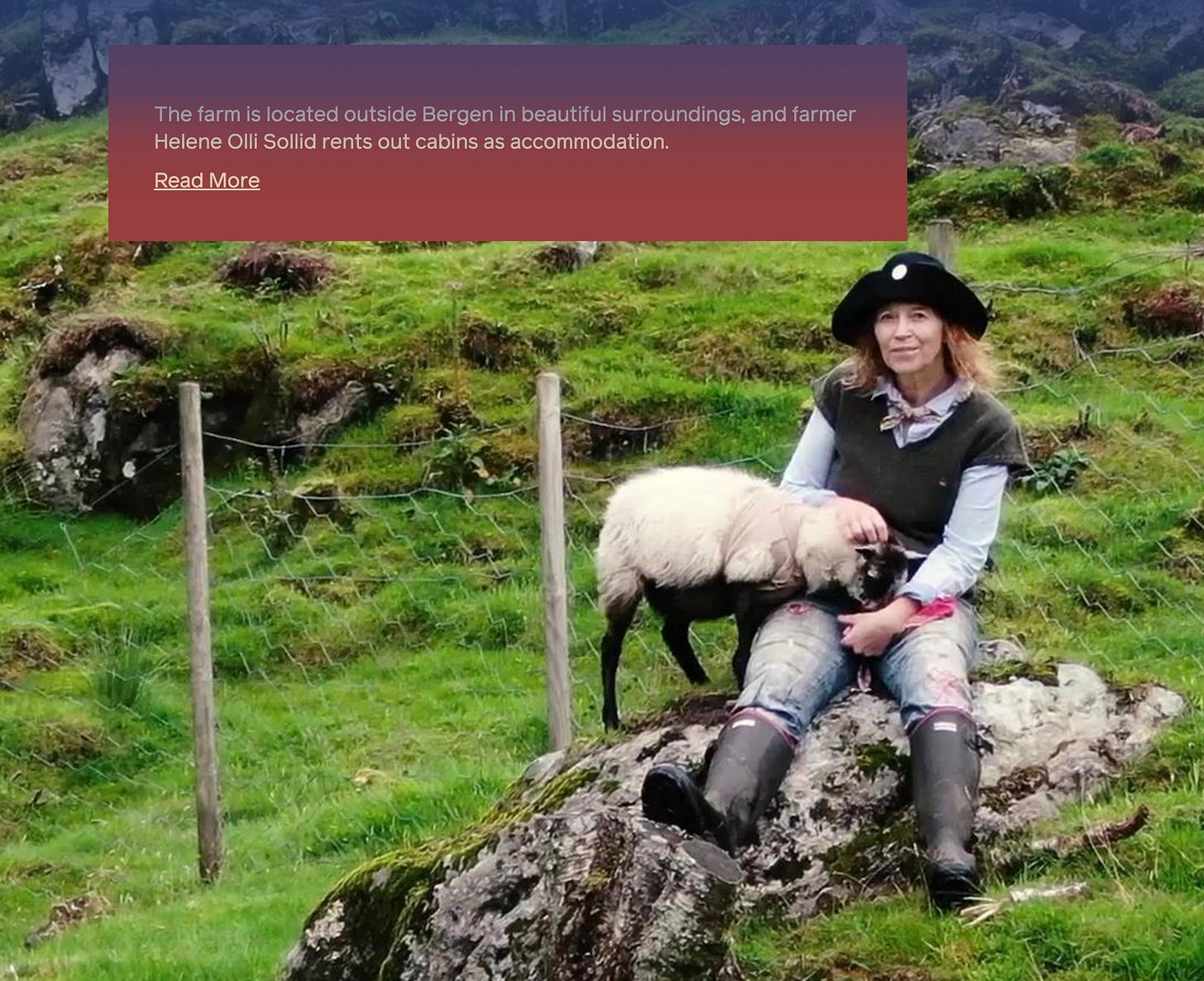

In Norway, local chapters of the Norwegian Association of Sheep and Goat Farmers collect and process members’ fleeces - it is not a commercial operation. The Norwegian government heavily subsidises wool production. Visitors to Norway are encouraged to celebrate and learn about wool, from the farm, to designer outlets, to the Viking wool heritage trail, - there is even a contemporary artist making soft sculptures from it.

In Scotland, in contrast, many crofters simply burn or bury their wool - it is virtually worthless. Most crofters are conttacted to sell their fleeces to British Wool. This was formerly the British Wool Marketing Board, a government-funded body which guaranteed a basic price to farmers. In 1993, British Wool became a non-profit operating without any government subsidy. BW pays the farmers about 50p a fleece - but it costs £2.50 to get a sheep sheared.

I asked a question in a crofting newsletter earlier this year about what people were doing with them and got a couple of replies.

Michael Foxley, a crofter from near Fort William, wrote: “I have about 100 ewes and gimmers producing 3 sacks of wool. The uplift by the British WMB was infrequent, delayed and finally non-existent. For the past 3 years I have been putting the fleeces into paths on boggy sections of my hill grazings or to protect young Scots Pine saplings in a woodland. My last cheque was for £50 for 3 sacks of Cheviot and Blackface - due to the failure to uplift I must have moved them around the barn about 10 times - always in the wrong place! My crofter friends all burn or bury their wool.”

Rachel Challoner a crofter in Fair Isle, replied: “Last year I sent 65kg and received £101.75 so it’s still definitely worth our while up here in Shetland to send our fleeces off! “ Rachel keeps mostly pure Shetland sheep but also a small number of Shetland/Texel crosses. The fleeces from the crosses go to Jamieson’s of Shetland - the last remaining spinning mill in Shetland. The fleeces from the pure Shetlands go to Uist Wool, a small spinning mill in North Uist, where they’re spun into skeins that she can then sell to bring in some income to support the croft.

Why is it worth so little? Wool is a terrific material, natural, hard-wearing, fire-resistant. It keeps its warmth even when wet and is naturally breathable. As well as being used for clothing and rugs, it also makes a great alternative to plastic Kingspan for insulating houses (though it needs to be treated to make it mouseproof). Michael Foxley bought some insulation wool from Wales to insulate his new roof and found it really effective “I could tear it with my hands - and it is great for fitting into irregular spaces.” Menopausal women are sometimes advised to use wool duvets because of their breathability.

British Wool processes and sells all the wool it produces at auction, and it mainly ends up in carpets. I spoke to a representative who told me that the issue is the tough global market - they get the best prices they can. He said a collective of farms in Wales buys their own stuff back as yarn from British Wool and they make items to sell in their farm shops.

Unlike Norway, Scottish wool doesn’t really have its own brand - perhaps that is part of the problem. As with many artisan products, the solution lies in telling a story, and conveying to people what is special about a natural product and why it is more expensive than synthetic alternatives - which are a by-product of the fossil fuel industry.

Wool is labour-intensive. It has to be scoured, washed, spun and then woven or knitted, either by hand or by machine. Knitting used to be a common pursuit - I remember my mum telling me about a nursing colleague from Fair Isle who could knit with one hand as she walked around the wards, with the other needle stuck in her belt.

For centuries, knitting was an important skill. We were liberated from the need to do it by the advent of materials made from petrochemicals, which can easily be turned into cheap, mass-produced garments. So convenient. How much time we save.

But it turns out that we who no longer need to knit are the losers. Knitting reduces anxiety, it creates a sense of satisfaction and it improves cognitive function, even perhaps staving off dementia. None of those claims can be made for the replacement activities of doom scrolling on social media.

Of course, there are people all over Scotland who do value wool and who are trying to do something about this situation ( eg the Falkland Blanket). The place where this is done with the greatest success, ironically, is Shetland. They have their own brand, a world-renowned technique called Fair Isle and even a festival. Shetland Wool Week is known in particular for its hats - every year a designer releases a pattern for a hat that people round the world can knit as a way of partipating. They are beautiful and colourful. Ashley Jensen would rock one. Perhaps someone should tell BBC Scotland.

Those of us who have spent years watching movies and tv programs about war, battles, and combat have had to cope with this for years - kings, princes, knights, etc. all fully armored and possessing an incredible array of armed supporting cast invariably appear bareheaded - skipping the period variant of head protection that kept the original personage alive in battle long enough to make a record that someone latter would decide warranted a movie - meanwhile, the agents, directors, producers, etc are all complaining that the helmet or headgear is hiding the face of their very expensive talent!

There is another question to be asked “ why does Scotland ignore indigenous takent , small businesses and industies in favour of shiny tec things?

There is a bias by Government against great local successes. The push , supported by many, many millions from the public purse is for “ scale ups, unicorns and tech.

Currently about £49 million pounds is being ploughed into helping Scottish tech businesses grow.